Occam’s Razor to FX: The Cyclical / Structural Framework

Beyond Carry and REER

This post is an excerpt from our October 2, 2023 thematic report to VP clients. The full length, original report can be viewed here.

A first principles approach to understanding FX

"Never, ever invest in the present“ – Stan Druckenmiller

This report presents a framework for thinking about the medium to longer-term outlook for FX. We deliberately exclude tactical inputs and explicitly focus on FX drivers on a 1 year forward basis.

FX markets have many good rules of thumb. Carry and valuations are key drivers; however, by incorporating the capital cycle, current account, fiscal policy and credit growth, we can offset some of the short-comings of carry and valuations.

It can sometimes be unclear how these different FX drivers interact and if there are implicit dependencies. We build intuition by leveraging random forest data science techniques to highlight interaction features.

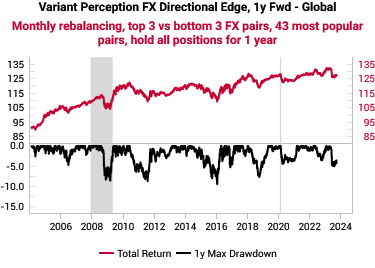

We then formalize these insights into a symmetric set of decision rules to create a quantified expected 1y forward “edge”.

Problem: the “scapegoat theory” of FX

Our brains are wired to spot patterns, even in randomness. This is a particular problem when trying to understand the complexity of FX markets given the many possible drivers and narratives.

ECB researchers call this the “scapegoat theory of exchange rates” (link to ECB paper).

Market participants are prone to shifting the importance attached to different macro variables to explain FX movements.

This results in short-term FX narratives that flip-flop depending on recent correlations (rates, policy, flows etc.). This could also explain the heavy focus in FX markets on market timing and technical analysis.

Problem: carry is king… until it isn’t

Historically, FX carry has worked as an investment strategy, especially pre-GFC (high-yielding currencies are correlated to higher total returns).

However, since the GFC, the carry vs return relationship has weakened dramatically. Some prominent examples are the Turkish lira (TRY) where total returns were negative despite very high carry and the Swiss franc (CHF), which strengthened despite negative carry.

FX carry is now subject to much more frequent sharp drawdowns. We suspect this is due to the strategy missing other key drivers of FX (such as fiscal policy and capital cycles) as well as becoming more crowded after a sustained period of great performance.

Another issue is that for most EM and some G10 currencies, carry strategies can generate the same long/short signal all of the time, effectively doing a buy & hold on high-yielding EMs through thick and thin.

Problem: “in the long run we are all dead” waiting for REER

Consensus long-term FX frameworks today are narrow, mostly concentrated on mean-reversion to an equilibrium level based on REER (real effective exchange rates) or PPP (purchasing power parity).

This framework is not wrong. REERs are indeed correlated with forward returns; a currency further below its 10y REER average tends to appreciate more.

However, in practice, currencies can deviate from “equilibrium” for a very long-time. In the case of EM, REERs should in theory even rise over time to converge with DMs (rather than mean-revert).

Other well-known relationships like terms of trade also have weak-to-no correlation to forward FX returns.

Academic estimates of the half-life of PPP have been estimated to be at least 3-5 years (link, link) i.e. it takes 3-5 years for the deviation from PPP to decay by 50%.

Solution: include Capital Cycle + Fiscal + Credit

We are not trying to re-invent the wheel. Interest rate differentials and valuations are key cyclical/structural drivers of FX markets, but by incorporating the capital cycle, fiscal policy and credit growth, we can offset some of the short-comings of carry and valuations.

Cheap currencies can stay cheap due to capital abundance. Rate differentials without the context of fiscal policy are also an incomplete picture. The Mundell-Fleming model is an example of a theoretical framework to understand the impact.

In this report, we explicitly focus on the cyclical to structural time horizon, which we define as at least 1 year forward.

As such, we are optimizing our models for 1 year forward expected outcomes. Our back tests use 1 year vintages (i.e. hold each new position for a fixed period of 1 year).

The key inputs (all relative): interest rates, capital cycle, M2 growth, fiscal balance, current account balance, REER.

what do you mean by "In the case of EM, REERs should in theory even rise over time to converge with DMs (rather than mean-revert)." ?

what does the "rise" mean, the best if you can answer on a concrete case.