The Structural Limits of Fiscal Policy

The theoretical limit is inflation, but the practical limit is politics

This post is an excerpt from our April 24, 2024 thematic report to VP clients. The full length, original report can be viewed here.

Scarcity? What do you mean scarcity?

“The first lesson of economics is scarcity: There is never enough of anything to satisfy all those who want it…the first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics”

-Thomas Sowell

The last 100 years have seen a relentless trend towards greater government spending and involvement in the economy.

Politicians usually prioritize quick results to appeal to voters who are focused on recent quality of life improvements.

The immediate benefits of fiscal spending, like low unemployment and rising GDP per capita, typically manifest quicker than the negative consequences, such as inflation.

This preference for short-term economic growth through deficit spending has often overshadowed the importance of long-term economic health.

Over time, as debt increases, so do the interest payments, necessitating additional financing and leading to an inflationary bias in Democratic governments; this allows the repayment of loans with devalued money.

Inflation? What do you mean inflation?

The inflationary impacts of government spending are well documented in economic literature. Even proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) view inflation as a constraint on fiscal deficits as the economy reaches full employment.

The danger historically is that when inflation does become a problem, politicians can try to “finesse” the problem by changing the system rather than make “hard choices” in the form of fiscal austerity.

An example of a “smaller” scale system change was the 1983 substitution of "owner equivalent rent" for real home-ownership costs in the calculation of CPI. ShadowStats estimate of inflation for today as if it were calculated the same way it was in 1980 (blue line, top chart) shows a much higher CPI than the current calculation methodology.

An example of a “larger” scale system change was 1971, when the U.S. halted the conversion of foreign-owned dollars into gold to combat “unacceptably high” 5% inflation.

This marked the end of the Bretton Woods system and beginning of the fiat system, which has given governments the ability to effortlessly create the most important commodity on the planet – money – and with it, increasing amounts of power.

Hyperinflation is the ultimate tail risk to excess fiscal spending

Apart from the 2 world wars, hyperinflation episodes have only occurred post-1971 (the end of Bretton Woods and beginning of the modern fiat system).

Peter Bernholz’s analysis of 29 periods of hyperinflation throughout history shows that in all cases, hyperinflation was marked by the financing of huge government deficits, defined as deficits exceeding 40% of government expenditures.

We are not there yet, but the trend in recent deficit spending is clearly up.

Hard money constrains government expenditures

Prior to the WWII, deflation was the norm in the US outside of major wars. This was due to the gold standard.

Under hard money systems like the US gold standard, the money supply is limited to the amount of a physical asset (e.g. gold) held in the governments vaults.

During periods of economic expansion, when the economy could naturally grow faster than the supply of gold, the money supply became constrained, leading to deflationary pressure. Hard money systems also have a psychological affect on savers, who know that over time, the value of their savings will increase.

Deflation causes the real cost of debt to increase. This is the exact opposite of the incentives for a government that can print its own currency.

Great Depression: end of hard money, sews seeds for modern welfare state

Central bankers in the era of the Great Depression staunchly supported the gold standard to ensure monetary stability, maintaining high interest rates to defend their currencies’ gold parity even after WWI.

This commitment restricted credit access, contributing to leverage and speculative bubbles, culminating in the financial crash of 1929.

Despite the Depression, central banks like the Bank of England emphasized their independence, highlighted by Governor Montagu Norman’s 1933 assertion to the BoE’s emeritus economist “you are not here to tell us what to do, but to explain to us why we have done it”.

The Depression intensified the already shifting public preference from laissez-faire to progressive economic ideologies stemming from elite overproduction during the industrial revolution.

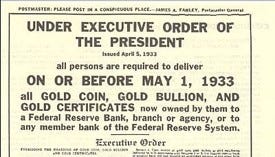

FDR campaigned in support of the gold standard but quickly abandoned it in 1933 to mitigate debt deflation, marking a significant move away from global hard-money systems.

Roosevelt’s policies, starting with the prohibition of gold hoarding and extending through the New Deal, laid the foundations for modern government economic intervention and the welfare state.

Money is the greatest story ever told…

For the fiat system to work, citizens need to have faith in a nations currency.

This requires trust in the countries economic policy and the people making that policy… or more simply put, the story the government tells you.

“Money is probably the most successful story ever told. It has no objective value: it’s not like a banana or a coconut that you can actually do something with. If you take a dollar bill and look at it, you can’t eat it, you can’t drink it, you can’t wear it — it’s absolutely worthless…

We think it’s worth something because we believe a story. We have these master storytellers of our society, our shamans. They are the bankers and financiers and the chairperson of the Federal Reserve and they come to us with this amazing story, that ‘You see this green piece of paper, we tell you that it is worth one banana.”

- Yuval Noah Harari

… and policymakers are the narrators

The success of policymakers’ actions (and ultimately their inflationary impacts) crucially relies on their ability to convey the intended effect to households and steer their expectations accordingly.

Politicians achieve this by justifying spending in many forms, but primarily in the name of “helping the greater good”.

“I have directed Secretary Connally to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets… Now, what is this action—which is very technical—what does it mean for you?

Let me lay to rest the bugaboo of what is called devaluation. If you want to buy a foreign car or take a trip abroad, market conditions may cause your dollar to buy slightly less. But if you are among the overwhelming majority of Americans who buy American-made products in America, your dollar will be worth just as much tomorrow as it is today. The effect of this action, in other words, will be to stabilize the dollar.”

– Richard Nixon, 1971

To read the rest of the report, contact us here.