Understanding The Kalecki-Levy Corporate Profit Decomposition

The Kalecki-Levy profit decomposition is a first principles way to understand the drivers of corporate profit margins using top-down economic flow data

This post was originally shared with VP clients on June 13, 2024.

A Top-Down Approach to Understanding Corporate Profit Margins

The Kalecki-Levy profit decomposition is an accounting identity that can explain the top-down drivers of economy-wide corporate profit margins.

It is not a leading indicator and does not provide a view into the future. However, it is a very useful mental model to think through implications of big macro drivers like fiscal policy and household behavior.

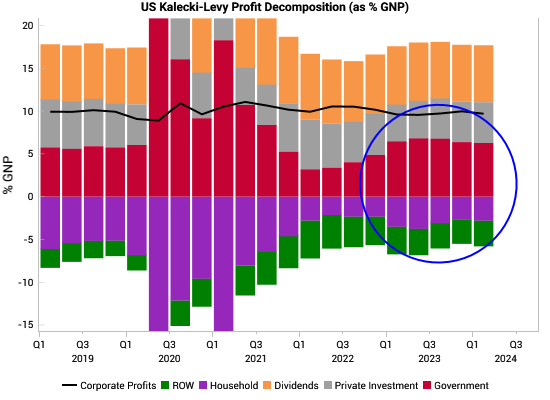

For example, US macro data throughout 2023 and early 2024 was consistently contradictory on the surface, with a resilient consumer and growth in the face of negative trends in credit and private investment. A Kalecki-Levy decomposition shows that this was enabled by the large fiscal deficit at the same time households were drawing down savings.

The Mechanics of the Kalecki-Levy Equation

Developed from the insights of Michal Kalecki and Jerome Levy, this profit margin equation is rooted in the idea that profit generation is a macroeconomic phenomenon affected by aggregate saving and investment behaviors. Their work laid the groundwork for viewing corporate profits through the lens of national accounts and economic interactions.

Corporate Profit = Investment + Dividends – Household Saving – Government Saving – RoW Saving

The components of the equation are:

Investment: Represents new capital formation plus changes in inventories.

Dividends: Money paid to shareholders, reflecting a distribution of profits.

Household Saving: Excess of household income over consumption.

Government Saving: The surplus or deficit of government budgets.

Rest of the World (RoW) Saving: Net savings from foreign entities, influenced by trade balances and other transfers.

The equation shows that corporate profit equals total investment plus dividends, minus savings (households, government and rest of the world).

To build intuition, we need to think through a few steps.

Firstly, when an economy is at equilibrium, savings must equal investment:

Saving = Investment

When people earn money, they can either spend it (consumption) or save it. The money people save then goes into banks who can lend this money to businesses. Businesses borrow this money to buy equipment (i.e. investment) to grow. For these flows to balance, the total amount of money saved by people must equal the total amount of money businesses borrow for investment.

Savings can be split into sectors:

Saving = corporate saving + household saving + government saving + RoW saving

Corporate Saving is simply corporate profit minus dividends:

Corporate Saving = Corporate Profit - Dividends

With a little substitution and rearranging, we end up with the Kalecki-Levy equation:

Corporate Profit = Investment + Dividends – Household Saving – Government Saving – RoW Saving

Using the Fed flow of funds data, we can empirically prove this relationship is true going back decades.

This framework is essential for understanding the top down nature of what drives profits and profit margins. This is a distinct approach to traditional bottom up accounting that goes through a company's income statement and utilize revenues, expenses (D&A, interest, wages) and taxes.

Tangible examples of using the Kalecki-Levy mental model

One example of using the Kalecki-Levy mental model is to think through a corporate tax cut. The first order impact of a cut to corporate taxes would be a rise in private sector corporate profits. However, this would result in a loss of government revenue that would need to be funded.

If the government funds the tax cut by issuing more debt, they would be increasing its deficit (i.e. government dissaving), which will boost profits on a flow basis.

If the government funds the tax cut by reducing other expenditures by the same amount as the lost taxes to keep the deficit unchanged, then in aggregate, the corporate sector will lose that amount in revenue. Consequently, the boost in profits from the tax elimination would be negated by the reduction in revenue, effectively nullifying any net gain in profits.

In practice, this means that changes in government savings and household savings tend to be the major top-down drivers of private sector corporate profits.

The unprecedented combination of household dissaving and government dissaving (fiscal deficits) over the past 12-18 months has helped to support US corporate profit margins and is set to persist absent a deterioration in the labor market and/or shrinking deficits (see our Fiscal Limit thematic to see why the latter is structurally unlikely).

The Fed Flow of Funds

The Financial Accounts of the United States, formerly known as the Federal Reserve's Flow of Funds Accounts, provide a detailed analysis of financial activities in various U.S. economic sectors like households, businesses, governments, and financial institutions.

Developed by Morris A. Copeland during World War II, the system was created to better understand sectoral financial flows to support wartime funding needs. Copeland's initial work at the Federal Reserve Board continued post-war at the National Bureau of Economic Research, leading to a system that could track financial sources and uses unlike traditional statistics like GDP.

Officially adopted by the Federal Reserve in 1955, the Financial Accounts of the United States currently include “data on transactions and levels of financial assets and liabilities, by sector and financial instrument; full balance sheets, including net worth, for households and nonprofit organizations, nonfinancial corporate businesses, and nonfinancial noncorporate businesses; Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts; and additional supplemental detail.”

Source: Federal Reserve

Kalecki-Levy in Practice - 1994 Analog Case Study vs Today

In our March G3 LIW, we used the Kalecki-Levy profit decomposition to analyze comparisons being drawn for today's economy to the economy of the mid-1990s.

We argued that today’s labor mismatch is more prominent while fiscal deficits look set to persist, suggesting more inflation risks today than in the 90s. We did so in part by using the Kalecki-Levy decomposition to show that the mid-90s disinflationary growth was supported by surging private investment (rise in red area in below chart).

At the same time, fiscal deficits declined and became a surplus (fall in red area in below chart), while households reduced savings from elevated levels and consumed more (purple area in below chart).

Today, private investment has room to rise, with the post-GFC period showing much lower levels of private investment vs history. However, there are few signs of fiscal prudence, while household savings rates are already low. This suggests that if fiscal stimulus remains, the main risk is inflation.

To read more of our research, contact us here.