Wage Pressures Building

Our US leading indicators point to higher wage growth as employers pay up for better quality labour in the wake of the pandemic. A nascent rise in trade-union density suggests the wind is changing and that we may see more structural inflation risks coming from the labour market

Labour costs and rising wages are becoming a growing concern, with earnings rising in many countries across the world. The pandemic and the policy responses to it - including direct fiscal support for earnings - have led to the dynamic of wages continuing to be biased higher, even while in many cases unemployment rates remain well above their pre-pandemic levels.

In the US, labour costs are becoming a growing concern, with firms most worried about rising labour costs from an input-cost perspective. Many firms are already experiencing rising labour costs.

Leading indicators for US wages agree. The rising Quit Rate suggests workers are confident enough of finding a new role if they quit, and this often leads to rising wages.

There are still almost two million extra people in the US on continuing unemployment claims than before the pandemic, so it might be expected that wage pressures would be subsiding. But it is clear from surveys that many small businesses (who account for almost half of US employees) are having difficulty filling positions.

The driving reason why businesses appear to be having this difficulty is poor quality labour. As a result companies are having to raise wages to attract better quality labour, especially in lower-skilled jobs.

This is reflected in the median wage for low-skilled occupations rising the fastest.

A lot of these jobs are in eg the hospitality industry, where many younger people work. It is only the 16-24 years age group that is seeing any wage growth at the moment.

We are also seeing the skill mismatch in the yawning gap between openings and hires, with the hires/openings ratio at series lows.

Research cited by the BIS (link here) showed that it is unlikely the generosity of unemployment benefits in the US is the reason for rising wages. The research looked at job applications/vacancy ratios by quartile of generosity in unemployment benefits, and found the ratio for the top quartile to be still higher in the Spring of 2020 than where it was pre-pandemic.

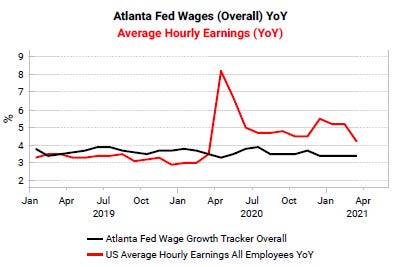

One caveat to note stems from the different types of wage measures in the US. The series with the longest history - average hourly earnings - suffers from compositional effects. In the first stage of the pandemic, many of the jobs lost were lower-paying jobs, which led to total hours worked falling faster than total earnings, ie average hourly earnings rose.

Now that the reverse is happening - ie lower-paid jobs are coming back - average hourly earnings are falling. This is why it is important to track other measures too, eg the Atlanta Fed Wage Tracker. This has been more stable through the pandemic as it takes the median wage and compares it to the median wage one year ago. We will see this measure rise if wages pressures in the US gather steam, as we expect.

In the Ocean Regime of greater inflations risks, the most important question is: will wage growth be inflationary? This depends in a large part on the bargaining power of employees, which is related to the degree of trade-union penetration. The US continues to have one of the lowest trade-union densities of OECD (+US) countries.

But this is changing. Favourable public opinion of trade unions in the US has been rising since the GFC and is at a joint high since the mid 1960s.

Furthermore, trade-union density is starting to rise in the US. The absolute number is still low, at 10.8% of the workforce, but the last two years has seen the largest rise since at least 1960.

In world where employees at a company such as Google have decided to form a union suggests the wind may be changing. This would represent - along with central-bank financed government spending and a slow reversal of globalisation - another major long-term structural driver of higher inflation.