The Age of Scarcity Part 1: The inflationary impact of government spending

In the coming decade governments will no longer hide behind the “invisible” hand of the market. They will be forced to make explicit choices on how society allocates resources. We think portfolios need to be positioned for structurally higher inflation. This will be a 3-part series based on the insights from our thematic report sent to VP clients in November 2022.

Since the 1980s, free market orthodoxy had effectively “de-politicized” economic policy. Governments were shielded from making decisions on resource allocation, leaving it up to the market’s “invisible hand”.

Today, the pendulum has swung back, with calls for the “political management of the economy” as we move towards an age of top-down government intervention.

The “Age of Abundance” since 1980 (with cheap credit, cheap labor and cheap commodities) is ending.

We turn to Hyman Minsky’s “political economy” work for guidance on how the next decade will play out.

For investors, the most important political development today is that credit allocation is shifting from the private sector towards governments. So far, we would characterize the developments as slow-moving, rather than an imminent policy shift.

The historical conditions necessary for a big policy shift (akin to FDR’s New Deal or Reaganomics) are not yet in place. Usually a major economic crisis is a key catalyst.

Activist governments and policy coordination with central banks often feature in, and contribute to, high inflation: inflation regimes often coincide with political regimes.

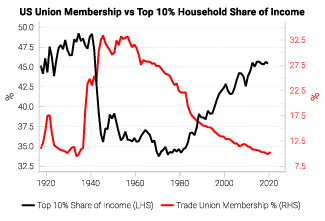

Hyman Minsky’s work on the role of institutions and wealth/income distributions helps us understand why. Looking at the shares of income going to the poorest vs richest households in the US, unanchored inflationary regimes see falling wealth concentration.

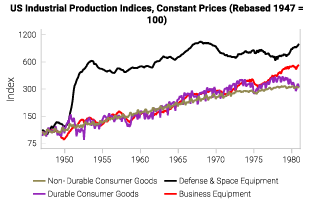

After World War II, the US government continued to spend very large amounts on defense. This resulted in “over-investment” in capital-intensive industries like aerospace and manufacturing.

The first order impact was to create “good jobs” in these capital-intensive sectors, but it also re-directed scarce resources away from investing in the consumer goods sector.

The second-order impact was to enable the mechanisms for future wage-price spirals:

“GM offered the UAW a contract which included… an automatic cost-of-living adjustment keyed to the general price index, and… a 2 per cent “annual improvement factor” wage increase” - UAW Bargaining Strategy and Shop-Floor Conflict: 1946-1970

In the post-war period, surges in real oil prices have been associated with stagnant productivity growth (left-hand chart). Today we are still in the midst of a structural commodity supercycle for energy (right-hand chart). The lackluster energy supply response so far bodes poorly for future productivity growth.

Politicization of credit + gov crowding out + energy crisis hurting productivity = structurally higher inflation.

On a 3+ year structural outlook, investors should focus on:

Real assets: useful upstream commodities in short supply, i.e. energy

Real estate and housing

Capex supercycle beneficiaries (part 3)

Higher “new normal” level of yields for nominal bonds

Gold and crypto are more complicated. They benefit from negative real rates as governments monetize their debt in a managed way. However, without obvious intrinsic value, the volatility will be very high (gold crashed 40%+ during the inflationary 1970s).

Get the full picture at variantperception.com

over the last 35 years public spending in advanced economies has barely dipped below 40% of GDP so the effectively de-politicized economic policy is an overstatement. Same goes for regulatory burden that subtracts to economic growth and disincentive to invest when we all know that technology is a major driver to productivity and growth. the rest of the analysis is spot on, though it doesn't mention the financial repression (negative real yields) we have already seen and we will keep seeing over time (70s style, Japan style)