Tracking the US's Labour Market Recovery

The US labour market has pockets of tightness. However, it’s unlikely we’ll see rapidly rising household inflation-expectations until we see higher low-skilled wage growth and rising ex-transfer incomes.

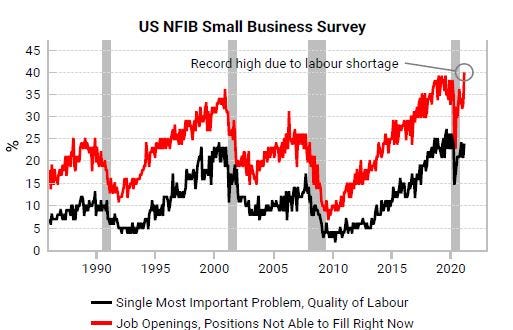

Our indicators show that at this relatively early stage in the recovery, the US labour market already has pockets of tightness and the huge amount of slack could be eroded more quickly than many expect given the strength of our US growth leading indicators. Last week’s NFIB surveys show that small businesses are finding it more difficult than ever to fill positions.

Job openings are back to pre-pandemic levels yet fewer people are willing to take them, creating an extraordinary divergence.

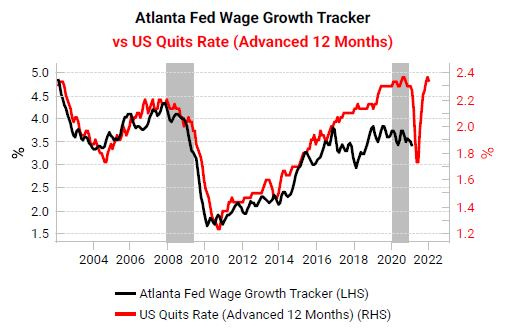

Part of this is due to rising quit rates. Normally this should lead to firms increasing wages to attract workers.

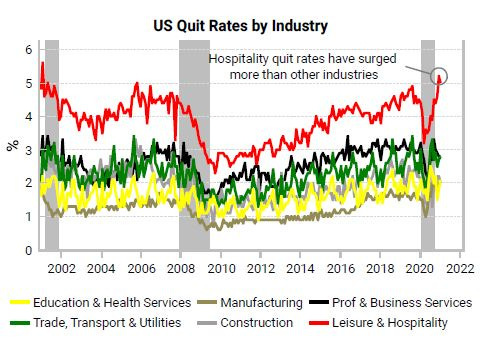

However, we see that quit rates have been propped up by people dropping out of the labour force, which is not a sign of labour tightness. Leisure & hospitality quit rates have increased the most.

Therefore imminently higher core inflation is unlikely in spite of the V-shaped recovery in total job openings.

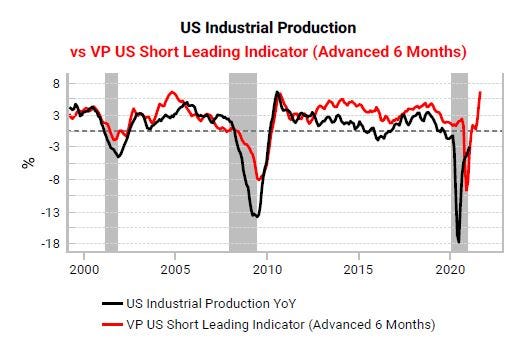

It has frequently been said that people are not filling vacancies due to enhanced unemployment benefits. A study by Yale economists in July 2020 found no evidence of extended unemployment benefits reducing employment .Still, it is troublesome that the US economy is experiencing a labour shortage problem so early into its recovery. This won’t be inflationary while jobless claims are still elevated. But once social restrictions are permanently eased, the labour market recovery could tighten quickly in line with the surge in our US leading indicator.

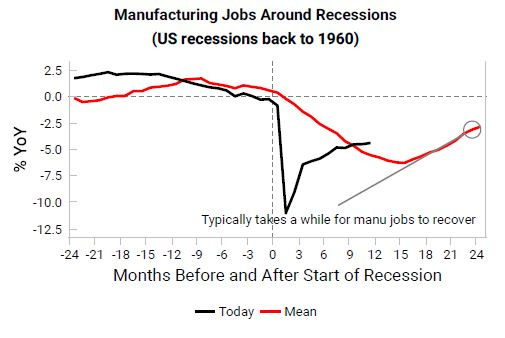

To date the gains in the labour recovery have been uneven. The “LUV” recovery we discussed last year (Biting Point - April 2020 Monthly) can be seen in the different sector’s job recoveries. Manufacturing has had a more V-shaped recovery compared to historical episodes.

Consumer-facing sectors have been experiencing a U-shaped or even more L-shaped labour recoveries.

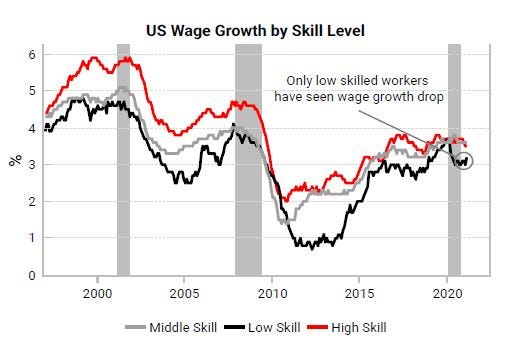

Low-skilled workers have seen their wage growth drop the most and are most likely to have dropped out of the labour force as a result of not being able to work from home.

This is why real incomes excluding transfer receipts are not rising.

The economy is less likely to get caught up in an upward inflation expectations spiral if personal incomes ex-transfers is not rising. This is a key variable that is tracked by the Fed and NBER when looking at the state of the business cycle. When real incomes start to increase, that is a signal that slack is being eroded and people are finding productive work.

While the labour market recovery has been uneven, we think the “U” recovery path of consumer-facing sectors will start looking like “V”s. Sector-level job data remains a useful signpost to track the labour-market recovery and will signal the first signs of persistently rising household inflation expectations.